Learning in High Dimension Always Amounts to Extrapolation

Context

-

It’s often said that learning methods perform better when interpolating the training data and worse when extrapolating it. This paper defies this notion.

-

Definition: A model interpolates if the input lies within (or on the face) of the convex hull “wrapping” the training data. The model extrapolates if the input is outside of this convex hull.

Takeaways

-

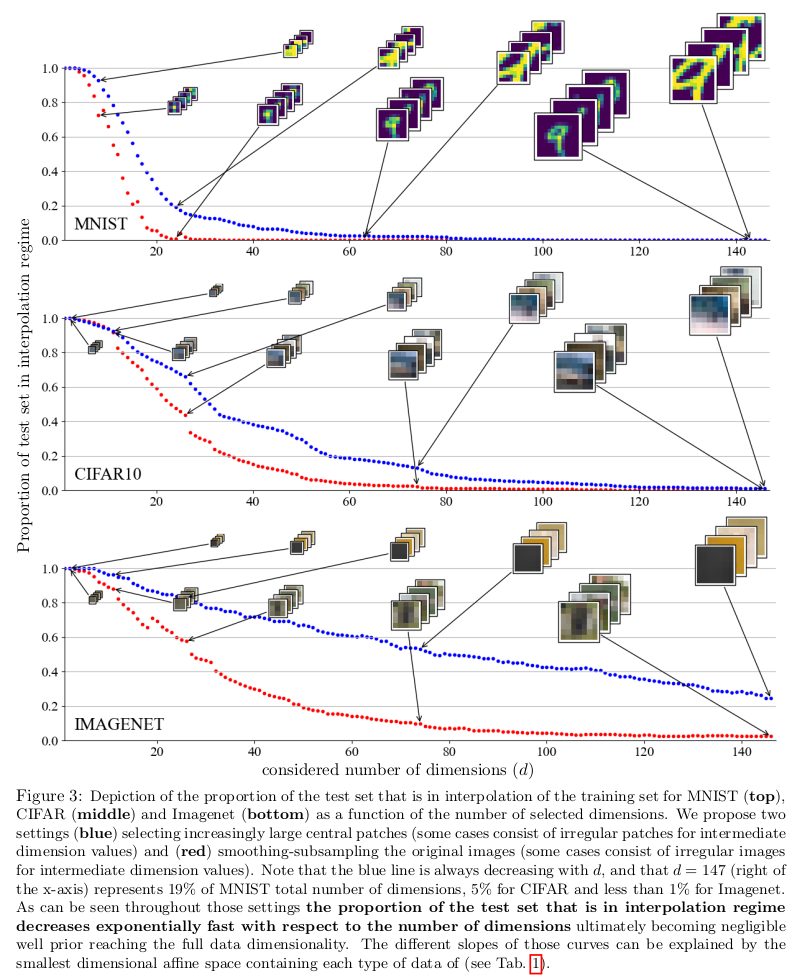

When learning in higher dimensions, interpolation rarely occurs. The models are almost always extrapolating. They prove that with theory and experiments using synthetic and real data.

-

“Higher dimensions” means more than 100. Even the smallest popular image datasets have more dimensions than that. For instance, MNIST has 784.

-

To remain in the interpolation regime, the training dataset size has to scale exponentially proportional to the data’s dimensionality.

-

Interpolation is unlikely to happen even in lower-dimension embedding spaces.

-

Since models like deep learning handle high-dimensional data well, and these models are almost always extrapolating, it follows that considerations about inter/extrapolation are irrelevant for predicting performance.

My remarks

-

The convex-hull definition of interpolation seems too strict to be useful in high-dimensional spaces. An extreme value at a single dimension (i.e. pixel) is sufficient to place a datapoint out of the convex hull.

-

The convex-hull criterium gives us a hard (binary) indication of interpolation.

-

A soft metric would probably be more helpful — something like the distance between the datapoint and the convex hull.

-

Such a metric may better predict the per-datapoint performance.